Dr Ben Marlow looks at research that suggests there is a subtype of autism where specific parts of the brain grow too much – and where there is the possibility of reversing the overgrowth.

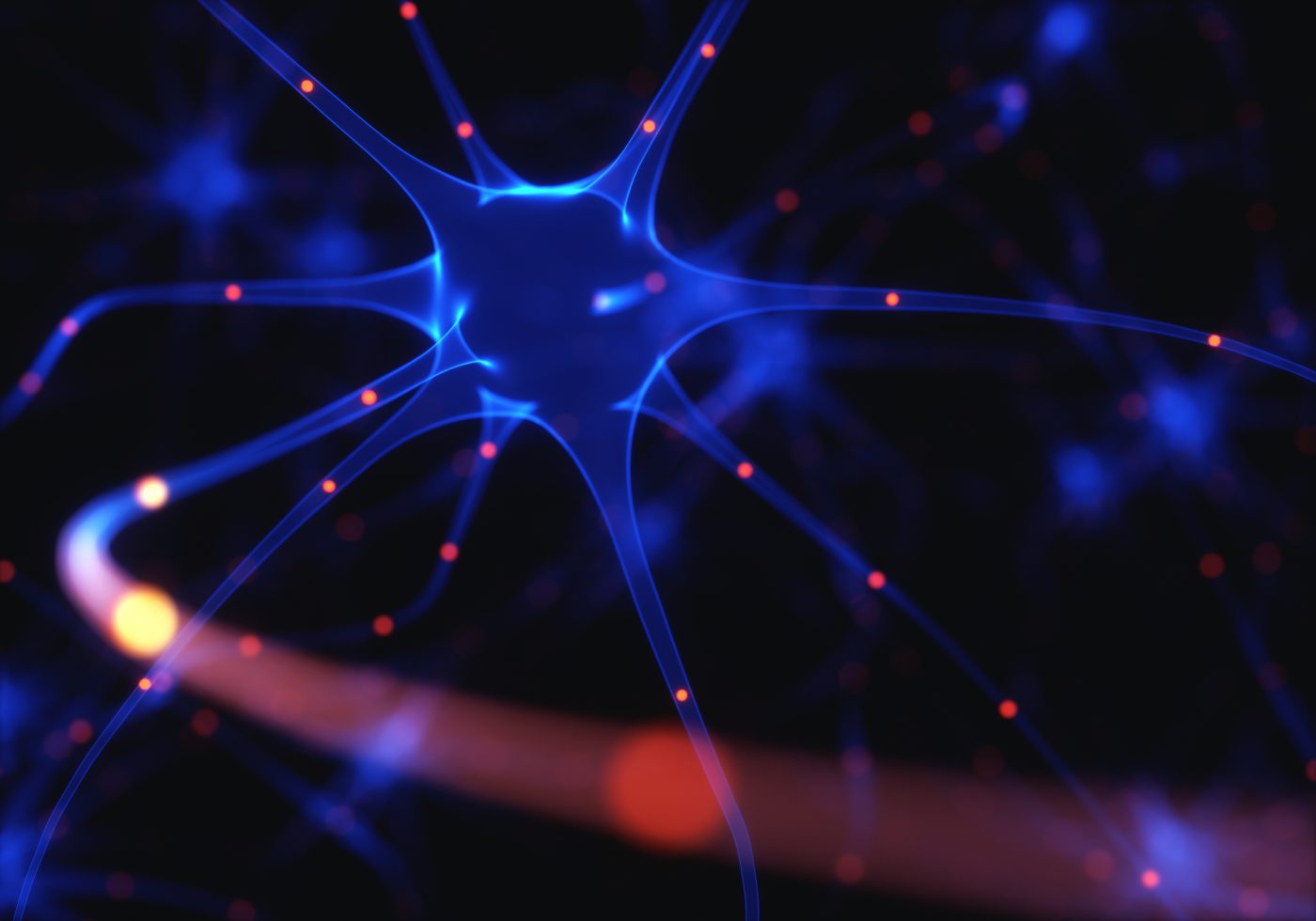

Looking around our garden at home we have a variety of flowers and trees interconnected with bushes and shrubs. Some are quite unruly, and if left unmanaged rapidly grow out of shape and increase in density. They start to block the light and be a nuisance. Pruning regularly keeps the correct structure: it provides a lighter density that affords other plants the ability to grow and be in balance. Imagine the brain is such a bush: the neurons and projections need constant surveillance and management otherwise they, too, become out of control. They turn increasingly dense and result in hyperconnectivity in the brain that isn’t required. Certain information is magnified in parts of the brain, with a resulting impact on behaviour and cognitive function. There is a subtype of autism linked to a dysregulated gene, called mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). It shows what can happen if the brain isn’t pruned correctly and the neurons start to grow in an unregulated and discordant way.

A recent study in mouse models(1), carried out using a combination of functional MRI scans and electrophysiological techniques, shows that ‘mTOR-dependent increased spine density’ (think bush overgrowth) is associated with autistic behaviour and hyperconnectivity within the brains of these mice. Importantly, drugs inhibiting mTOR were shown to completely reverse these behaviours. The team were able to correlate this finding to work in humans. It means that the drugs inhibiting mTOR have a potential therapeutic benefit for individuals with the subtype of autism where there is dysregulated mTOR expression.

Overactive mTOR gene

mTOR overactivity in the mice was brought about through using mice with a specific mutation in the tuberous sclerosis (TSC-2) gene. (Tuberous sclerosis is an overgrowth syndrome linked to intellectual disability and autism). The researchers mapped their brains using functional magneticresonance imaging (fMRI). It showed a higher density of dendritic spines (short protrusions from nerve cells) in the insular cortex (a brain region relevant to social dysfunction in autism) and in the prefrontal cortex. The images also displayed a distinct hyperconnectivity signature, showing large-scale over-synchronisation of neurons. The researchers gave an mTOR inhibitor, rapamycin, to the TSC 2+/- mice (with dense synapses and brain hyperconnectivity) in their fourth postnatal week. Incredibly, the medication reduced spine density to that of the control. Also, there was a complete rescue of the fMRI hyperconnectivity map and ASD-like behaviours back to those of the controls.

In short, the medication reduced the brain density (enabled the pruning), resulting in reduced brain regional hyperconnectivity on the scan. This correlated with a reduction in autistic behaviour. By improving/enabling pruning the unruly mass of connections was streamlined. It allowed the researchers to ‘turn down the volume’ and rebalance, which was also seen through a reduction in stereotypical behaviour.

Interesting signature

Crossing from mouse models to human studies, the team showed that a specific ‘fronto-striato-insular’ fMRI hyperconnectivity in certain children with autism mirrored that seen in ‘mTOR overactive’ mice. Further genetic analysis showed this specific group of children (Neurotype 2) not only had the same characteristic brain imaging signature, but also had an overexpression of mTOR genes. Being able to correlate a specific fMRI signature with both behaviour and gene expression profiles is very significant. This‘subtype’ of autism related to mTOR overexpression can be characterised neuro-physiologically, biochemically, behaviourally and genetically. The subtype could also, importantly, be amenable to pharmacological intervention. Seen through mouse models, this course of action resulted in a resolution of the abnormal brain density, hyperconnectivity and autistic behaviour. If ever there was an argument to subphenotype autism (define a subgroup with the condition) this is it. To define and understand unique brain imaging/ electrophysiological signatures and correlate them to a specific genetic change amenable to pharmacological therapy is perhaps the future.

Clinical trials

mTOR inhibitors (such as the drug everolimus) are already in clinical use. They are licenced for use with the related condition tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), an overgrowth syndrome where mTOR is also dysregulated. TSC is a condition that people are born with that often leads to non-cancerous growths developing in the brain, eye, heart, kidney, skin and lungs. TSC tumours of the brain can cause seizures. Seizures are one of the most common symptoms of TSC, which is also associated with intellectual disability and autism. Trials have shown(2) that everolimus can reduce seizure activity in patients with TSC. The treatment group showed a median seizure frequency reduction at two years, which is why (along with other evidence) the drug has been positioned as a therapy when more traditional anti-epileptics don’t work. Everolimus has been licensed since 2019. A trial in 2019(3) also looked at the effects of everolimus on children with TSC who didn’t have seizures. The researchers looked at outcomes relating to IQ levels, autistic symptoms, behavioural issues, social functioning, communication skills, executive functioning, sleep, quality of life and sensory processing. There were no significant differences between the drug and placebo on these outcomes, which was disappointing. The authors reflected that there may be a time-critical window where the drug has an effect: the mice models I have discussed were in mice four weeks postnatally, whereas the human trial was in an age range of four to 17 years.

The future

mTOR remains an interesting target for neurodevelopmental conditions, including autism. Mouse models suggest that a subtype of autism exists whereby there is overgrowth (synaptic density) in specific parts of the brain. This results in hyperconnectivity and over-stimulatory signals, leading to a specific signal on an fMRI scan that also correlates with autistic behaviour and overexpression of mTOR. The theory remains that switching that proliferative signal off could tame the overgrowth at the synapses. But there are still questions as to what age period this benefit would apply to, and how reliably one could subtype children with autism to know that their biology would be amenable to mTOR inhibition.

REFERENCES

- Pagani et al, 2021: ‘mTOR-related synaptic pathology causes autism spectrum disorder-associated functional hyperconnectivity’, Nature Communications 12:6084, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26131-z

- French et al, 2016: ‘Adjunctive everolimus therapy for treatment-resistant focal-onset seizures associated with tuberous sclerosis (EXIST-3): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study’, The Lancet 388:10056 2153-2163, https://www.thelancet.com/ journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(16)31419-2/fulltext

- Overwater et al, 2019: ‘A randomized controlled trial with everolimus for IQ and autism in tuberous sclerosis complex’, Neurology Jul 9;93(2):e200-e209, https://n.neurology.org/content/93/2/e200.abstract

Visit our USA website

Visit our USA website