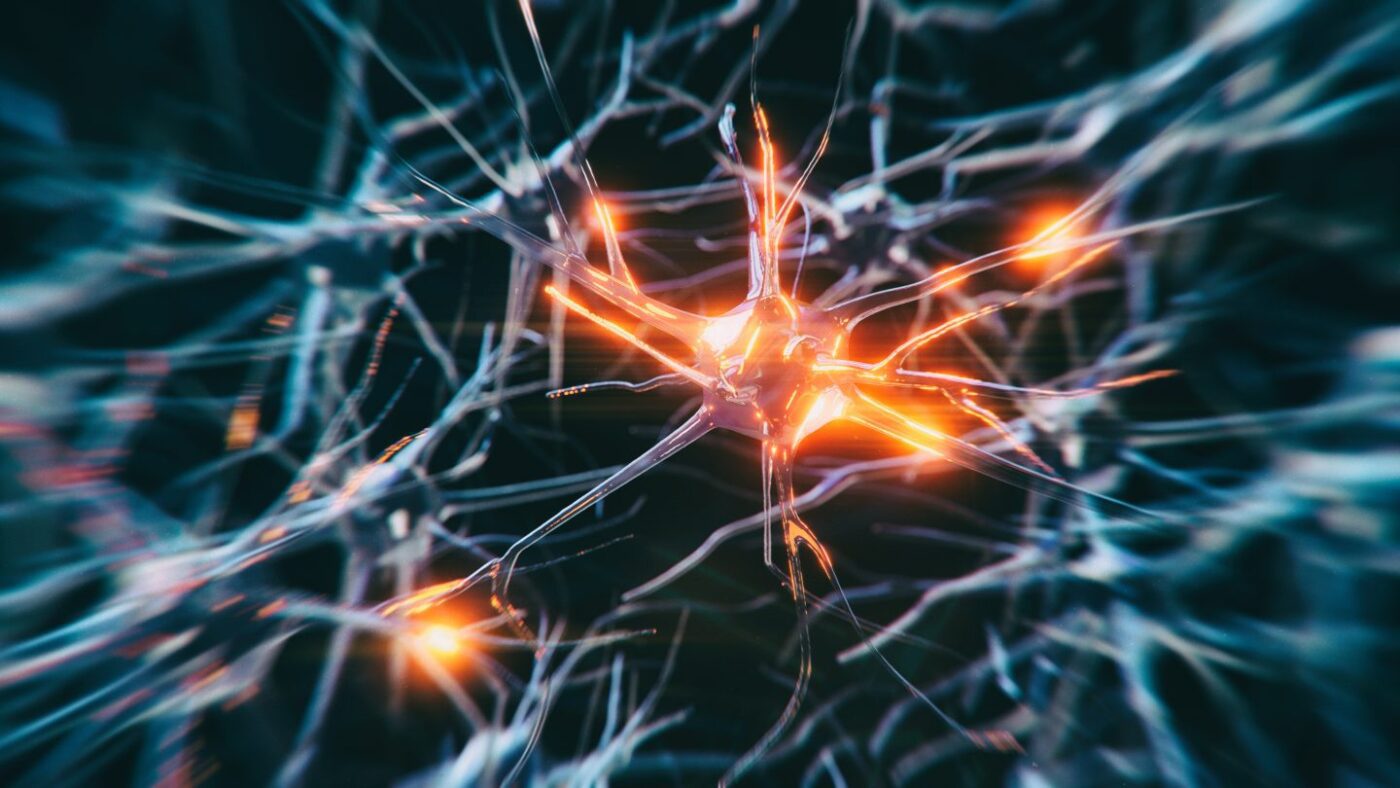

In my TEDx talk, I spoke about the brain’s hidden maintenance systems and why sleep is central to neurological health. This short piece looks back to one of the earliest thinkers who refused to accept that the brain’s waste “simply disappeared.”

Prof. Roy Weller had never trusted explanations that ended with the words “it simply disappears.” In science, that phrase was usually a confession, not an answer.

He learned this early in his career, standing in a quiet pathology lab, surrounded by microscopes and the faint smell of preservatives. The human brain lay before him, elegant, complex, impossibly alive even in stillness. Textbooks told him many things: how neurons fired, how blood fed the tissue, how electrical signals formed thought. But when Weller asked a simpler question—How does the brain remove its waste?—the books fell silent.

Every other organ had a system. The liver filtered. The kidneys cleansed. The body relied on the lymphatic system to carry away debris and toxins. Yet the brain, scientists said, had none. Waste products, including potentially dangerous proteins, were thought to diffuse away or be absorbed somehow, mysteriously, without pipes or pumps.

Weller frowned at that word: somehow.

As a neuropathologist, he spent his days studying disease, tumours, degeneration, inflammation. He examined the thin membranes surrounding the brain, the meninges, which most researchers treated as packaging rather than purpose. But Weller lingered there. He noticed channels. Patterns. Pathways where cerebrospinal fluid seemed to move with intention, not randomness.

Late at night, when the building emptied and the hum of equipment became a companion rather than a distraction, he traced these routes again and again. Fluid followed blood vessels. It flowed in ordered streams. It did not look lost.

“It looks like a drainage system,” he murmured once to himself, breaking the silence.

Colleagues were polite but cautious. The idea that the brain possessed a previously unrecognized clearance network was bold, perhaps too bold. Neuroscience was already crowded with theories, and the brain was famously resistant to simple explanations. Still, Weller persisted, not loudly, not dramatically, but patiently, publishing careful observations and asking careful questions.

Years passed. Technology advanced. New imaging techniques allowed scientists to watch fluid move in living brains. And slowly, almost shyly, the evidence began to gather.

Researchers observed that cerebrospinal fluid surged through the brain during sleep, flowing along arteries, washing through tissue, and exiting along veins. Waste proteins, those associated with Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders, were carried away more efficiently when the brain rested. Sleep, it turned out, was not only for dreams. It was for cleaning.

The system was finally given a name: the glymphatic system, so called because it relied on glial cells and functioned much like the lymphatic system elsewhere in the body.

When Weller first heard the term, he smiled.

A river, at last, had been acknowledged.

He liked to imagine it that way: a night river, invisible during the rush of waking life, flowing strongest in darkness. As the world slept, this river expanded its banks, washing away the debris of thought, memory, and metabolism. Every day left residue behind; every night offered renewal.

In lectures and conversations, younger scientists spoke of breakthrough discoveries and cutting-edge scans. Weller listened with quiet satisfaction. He did not claim ownership of the glymphatic system, but he recognized it as something familiar—an old question finally receiving a proper answer.

His work reminded him that science did not always move in leaps. Sometimes it moved like fluid itself: slowly, persistently, carving pathways through resistance.

In the end, Prof. Roy Weller remained what he had always been, a careful observer, a man who trusted patterns more than assumptions. He had followed the flow when others dismissed it as noise. And because of that, the brain was no longer a sealed city with no exit routes, but a living landscape with rivers, rhythms, and renewal.

Long after midnight, when Weller finally turned out the lights in his lab, the night river flowed on, quiet, tireless, and essential, cleaning the mind as it always had, whether named or not.

The idea of the brain as a living landscape, with rhythms, flows and renewal, continues to shape how we think about sleep, attention and disease. I explore this further in my TEDx talk, where I reflect on why rest is not passive, but fundamental to how the brain survives.

Watch the TEDx Talk:

Visit our USA website

Visit our USA website